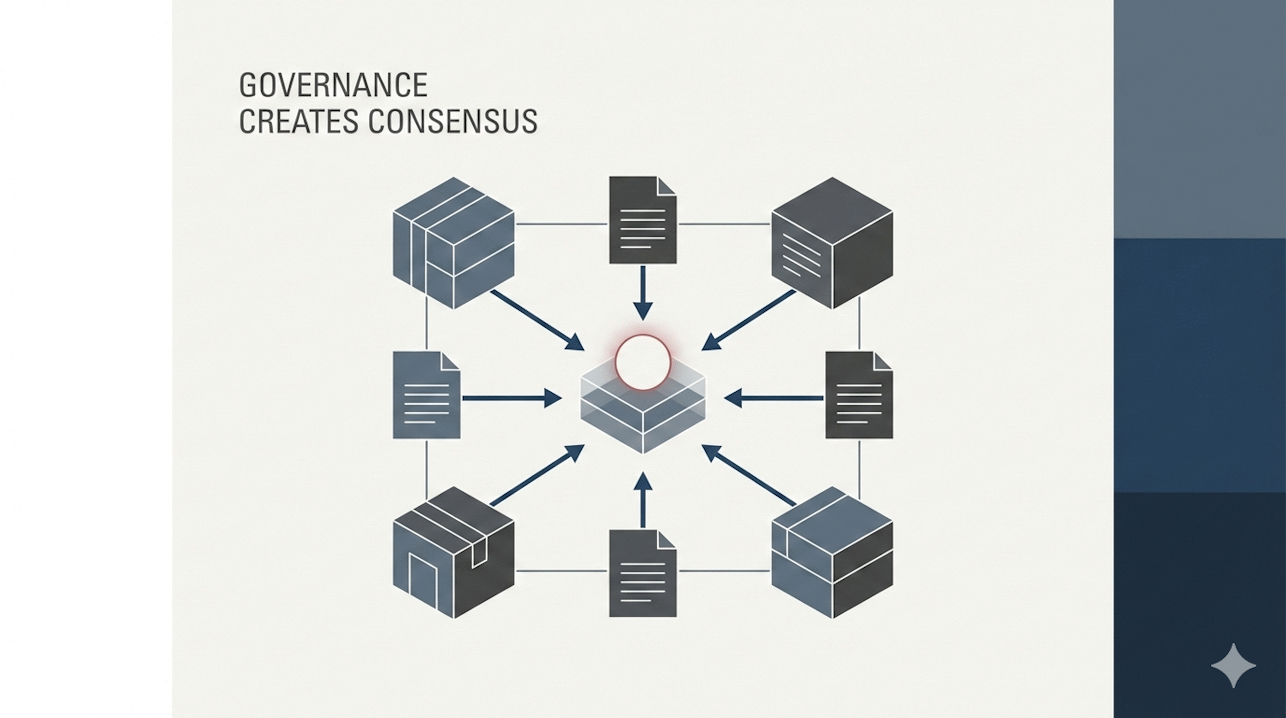

Blockchain discussions often jump straight into algorithms. Proof-of-Work, Proof-of-Stake, Byzantine fault tolerance. But consensus is not primarily a technical achievement. It is the outcome of governance.

Governance determines who sets the rules, who validates records, how disputes are resolved, and how systems evolve. Technology enforces consensus; governance defines it.

This distinction matters especially in regulated, high-trust environments like Switzerland, where clarity of roles and accountability are foundational.

What Governance Really Means in Consensus Systems

Governance is the human and institutional framework around a system, not the software.

In a blockchain or distributed ledger context, governance answers:

• Who can write to the ledger

• Who validates entries

• How rules change

• How disputes are handled

• How the system aligns with law and regulation

Consensus mechanisms express these decisions in code. Without governance, even the best-designed protocol becomes brittle.

Three Governance Models for Consensus

1. Centralised Governance (Traditional Systems)

A single authority controls records and enforces trust through institutional processes.

This model works well where institutions are trusted, but it struggles with:

• cross-organisational coordination

• reconciliation between siloed systems

• transparency across stakeholders

Blockchain does not replace this model, but it can complement it where shared verification is required.

2. Decentralised Public Governance (Open Blockchains)

Public blockchains rely on open participation and algorithmic consensus:

• anyone can validate

• rules are enforced by protocol

• governance evolves slowly and informally

They offer openness and censorship resistance, but at significant cost:

• high coordination and energy demands

• limited privacy

• unclear accountability

• weak regulatory alignment

For most Swiss institutions and SMEs, this model is rarely a practical fit.

3. Federated or Permissioned Governance (Most Practical in Reality)

This model aligns best with enterprise and public-sector needs.

Key characteristics:

• a defined group of trusted parties operates the network

• rules are agreed upfront, often contractually

• validation rights are distributed but controlled

• governance maps to legal responsibility

Examples include banking consortia, public-private platforms, and industry networks.

Swiss initiatives such as SIX Digital Exchange (SDX) and Swiss Post’s digital timestamping services illustrate this pragmatic, regulated approach.

In these systems, blockchain does not eliminate institutions, it coordinates them.

Why Governance Enables Consensus Without Full Agreement

Participants may distrust each other, compete commercially, or disagree on interpretation. Yet they still align on outcomes because:

• rules are explicit

• validators are known

• evidence is verifiable

Governance narrows disagreement to rule design, validator selection, and exception handling.

Once these are settled, day-to-day operations no longer require trust between participants, only trust in the framework.

A simple way to express this:

Governance → Rules → Validators → Evidence → Consensus → Trust

Consensus is the technical expression of governance decisions.

The Oracle and Input Problem

Blockchain secures records after entry — not truth at the source.

Governance therefore defines:

• who may input data

• how data quality is ensured

• how errors are corrected without undermining integrity

Most real systems use hybrid models:

• data stored off-chain

• hashes or proofs anchored on-chain

• predefined correction procedures

Without these rules, immutability becomes a liability rather than a strength.

Swiss Context: Why Governance Comes First

Switzerland already operates on strong governance principles:

• clear legal frameworks

• distributed responsibility across federal, cantonal, and municipal levels

• high institutional trust

Successful Swiss blockchain systems mirror these structures rather than bypass them. They:

• involve regulators early

• map legal responsibility to technical roles

• keep complexity invisible to end users

• prioritise auditability over disruption

In practice, governance determines whether blockchain reduces friction, or simply relocates it.

What This Means for SMEs

Governance may sound abstract, but for SMEs it directly affects daily operations.

A well-governed system delivers:

• fewer invoice or contract disputes

• clearer audit trails

• easier compliance

• predictable processes

Poor governance leads to:

• unclear responsibilities

• rejected or disputed records

• duplicated work

• loss of trust

For SMEs, governance is not bureaucracy, it is risk reduction.

Conclusion: Consensus Is a Governance Problem First

Consensus does not emerge from algorithms alone. It emerges when:

• rules are clear

• responsibilities are defined

• verification is shared

• accountability is explicit

Blockchain enforces consensus, but governance earns legitimacy.

In Switzerland, the most effective blockchain systems will not be the most decentralised or technically complex. They will be the ones whose governance models reflect how institutions already work, and quietly make coordination easier.

If consensus is the goal, governance is the starting point.